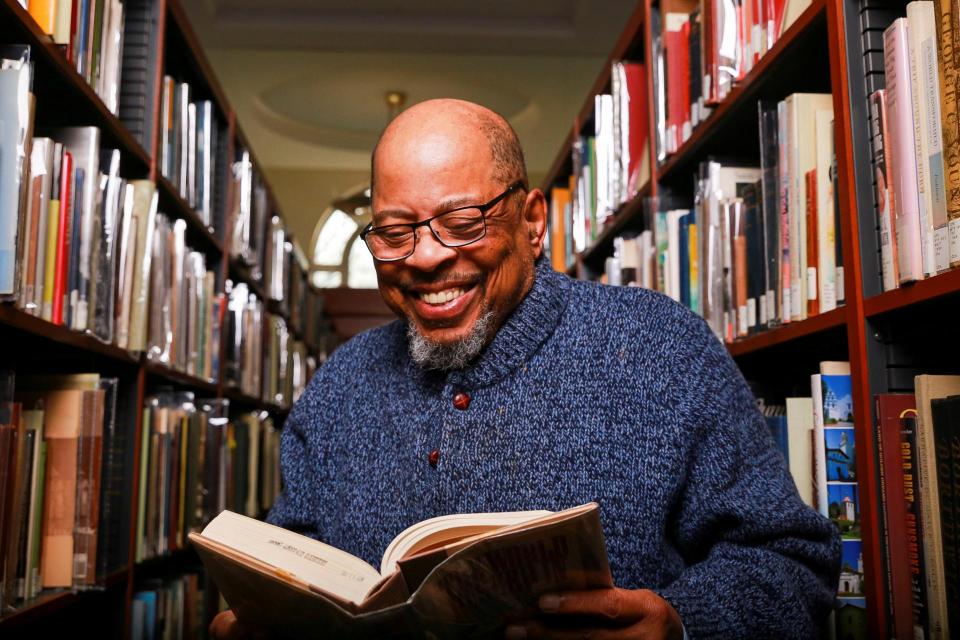

A Promise Kept

Judge Rudolph “Barry” Loncke

Keeping a promise isn’t always easy, but for Judge Rudolph “Barry” Loncke, keeping one made to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. became the work of a lifetime. One of the youngest African-American students to ever attend Yale, he met the illustrious leader of the civil rights movement when Dr. King visited the university to speak about racial inequality in America. In a moment he’ll never forget, Judge Loncke gathered his courage and approached what he recalls as a gracious, soft-spoken man sitting alone by the fire in the early hours of the morning. Wanting to know more about the  movement and how the reverend was fairing under such intense scrutiny, the young student was dumbfounded when Dr. King wanted to know what he was doing to contribute to the cause.

movement and how the reverend was fairing under such intense scrutiny, the young student was dumbfounded when Dr. King wanted to know what he was doing to contribute to the cause.

Unable to answer, the young student took away from that brief conversation a lifetime of desire to do more, and do it well. Still unsure of his own path, Judge Loncke carried King’s message of hope and civic engagement over the next several years, including a brief stint in medical school before landing in the jungles of Laos and Thailand as a radar operator during the Vietnam War. After six years of service with the Air Force, he returned home to a country divided. Urban cities were awash in civil strife, with Americans protesting against their own government and attacking one another.

Hoping to avoid the conflict, Judge Loncke opted to attend law school at Cornell, a distinguished Ivy League school nestled in the New York countryside. And yet, it wasn’t long before the conflict found him. In April of 1969, barely a year after Dr. King was assassinated and President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, Judge Loncke found himself in the center of an on-campus situation involving members of the African-American Society (AAS). Finding a burning cross on the doorstep of a residence hall for African-American students and receiving little response from the administration, members of the AAS occupied Willard Straight Hall in protest. After receiving numerous verbal and physical threats, the determined students felt the only way to ensure their safety and guarantee their grievances were heard was to arm themselves. The situation quickly escalated, with city and state police arriving in droves.

Knowing little of the situation, Judge Loncke was studying when he was approached by one of his professors. “He said to me ‘What are you doing, Barry? Why are you just sitting here when the whole world is on fire?’ I thought it would all blow over, but he insisted those kids were in danger. In mortal peril, he told me. And I realized how stupid I was, to think I could just avoid the issue, just stay up there in my ivory tower and ignore it.” Consequently, the young law student offered his help and the Cornell administration accepted gratefully. “They understood that what was happening was way more dangerous than just a protest. They understood the lethality, the danger those kids were in. So everything I asked for, they said ‘Do it! Just get them out of there and somewhere safe!’” So empowered, Judge Loncke then acted as mediator between an armed group of terrified African-American students and the police that surrounded them, negotiating their departure from the hall and their precarious walk across the university campus.

While several things came out of the confrontation (including the African-American Studies and Research Center at Cornell University and a Pulitzer-winning photograph depicting the students’ exodus from the building), Judge Loncke took away something quite personal and powerful—an underlying philosophy of life. “I learned I could not avoid the problems of the world. I wanted to help solve problems, but more than that, I wanted to help prevent problems from happening in the first place. And to advocate for people who are ‘under the gun,’ so to speak.”

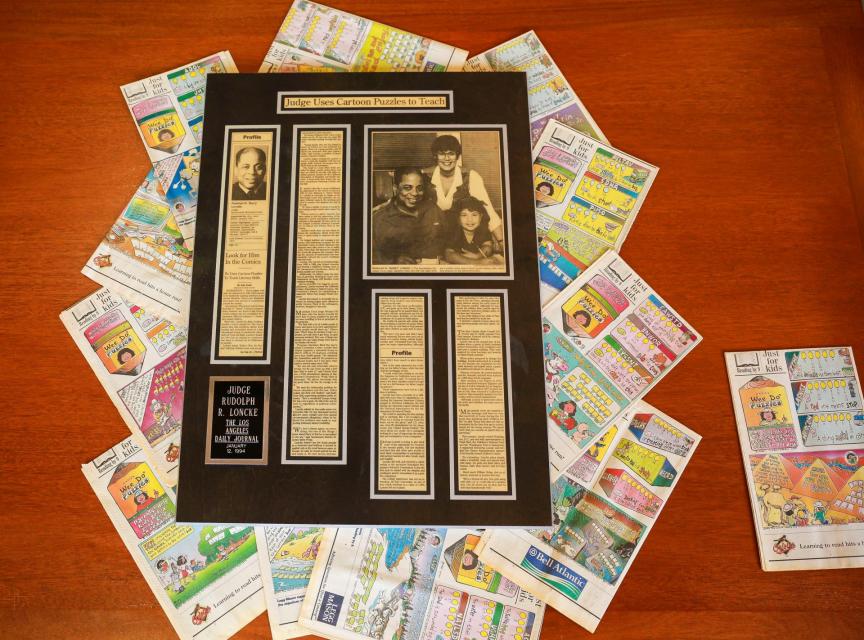

And advocate, he did. Appointed to the bench in 1981 by Governor Jerry Brown, Judge Loncke spent 21 years in the Sacramento Municipal Court fighting racial and ethnic bias in the justice system and pushing for significant improvement in the lives of African-American children. As part of the Steering Committee on the Reduction of African-American Child Deaths (RAACD), Judge Loncke pressed his fellow judges to consider the far-reaching implications for the children and families of those being prosecuted in their courts. In a 2015 Sacramento Observer article, Judge Loncke stated “Our state justice system could do a much better job of finding alternatives to prison for many of minority inmates convicted of non-violent crimes. A significant percentage of such offenders might contribute to the upbringing of their children as part of intact families.”

And advocate, he did. Appointed to the bench in 1981 by Governor Jerry Brown, Judge Loncke spent 21 years in the Sacramento Municipal Court fighting racial and ethnic bias in the justice system and pushing for significant improvement in the lives of African-American children. As part of the Steering Committee on the Reduction of African-American Child Deaths (RAACD), Judge Loncke pressed his fellow judges to consider the far-reaching implications for the children and families of those being prosecuted in their courts. In a 2015 Sacramento Observer article, Judge Loncke stated “Our state justice system could do a much better job of finding alternatives to prison for many of minority inmates convicted of non-violent crimes. A significant percentage of such offenders might contribute to the upbringing of their children as part of intact families.”

Beyond his focus on judicial reform, Judge Loncke found the prevailing attitudes amongst state politicians and policymakers regarding young African-American families were (and remain) counter-productive to implementing real change. “Instead of educating people to understand parenting and child development, they’re focused on funding some daycare program. That’s just a Band-Aid. We need to heal the wound.”

Rather than accept the status quo, Judge Loncke helped organize early human development education for young adults of color. “In my view, every parent should  know how the brain develops, and why the first three years of a child’s life are so important. That’s when everything is getting set up, everything is getting structured. If your structure is flimsy, it doesn’t matter how hard you try – you’re always going to be behind. The only way a brain grows in a way that will support future learning is by words.”

know how the brain develops, and why the first three years of a child’s life are so important. That’s when everything is getting set up, everything is getting structured. If your structure is flimsy, it doesn’t matter how hard you try – you’re always going to be behind. The only way a brain grows in a way that will support future learning is by words.”

Impossible to catalogue all the ways Judge Rudolph “Barry” Loncke has improved and enriched our region and community, this is but a glimpse into the life of a man who made a promise and lived his life keeping it. We are honored and privileged to consider a man of such integrity and grace part of the Eskaton family.